As mentioned before this is not strictly a Hugo category, it just uses the same voting system with the same electorate and is given out at the same time. It’s also an odd duck, as novels duke it out with short stories and mixtures of both. Still, the Campbell Award often ends up being my favourite slate – in previous years I have preferred the novels represented here to those in the novel category.

J. Mulrooney

An Equation of Almost Infinite Complexity [Novel]

An out of work actuary follows a suggestion from the Devil next door to get a job at an insurance company.

Satire is difficult – if you write a book about hateful shallow people doing stupid things, then it requires a deft touch to avoid your book becoming what it parodies. It’s hard to pinpoint exactly where Mulrooney goes wrong, as it hits all the notes of a theological satire of the suburbs, but I suspect that what is missing is some affection for the characters and the setting. The only redeeming feature of the book is the core plot driver, the possible existence of an equation that predicts when someone will die based on random phenomena in the world, but it’s too little to salvage the whole.

A satire in the vein of the Screwtape letters that completely misses the mark.

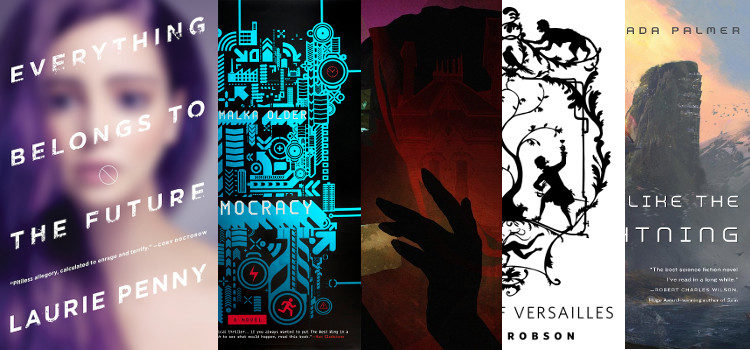

Ada Palmer

Too Like the Lightning [Novel]

An itinerant worker who wanders the halls of power of the 25th century narrates the tumultuous challenges of his era.

I come not to bury Caesar but to praise him. This book is incredible: it creates a fully realised future where ultrafast transport has disconnected geography and politics, it examines a wide gambit of issues both philosophical and theological in a society where religion is expressly banned as a group activity and sensayers act as non-denominational (or even non-religous) priests to the populous, it is consciously written to evoke the 18th century while constantly contrasting it with the mores of the future, and it has an engaging plot that braids together a boy who can command miracles and competing political conspiracies. I suspect this will be a seminal book for many people, and expect it will reward multiple reads.

For me however, this book was a chore. From the very beginning something felt off to me, like there was no emotional core to the story. Mycroft the narrator, is perfectly pitched, unreliable in spots, personable, and constantly breaking the fourth wall. But the narrative is too showy, like a stage magician who is incredibly competent, but punctuates every trick with “see what I did there, isn’t it great”. For example, Palmer constantly plays with gender, noting that in the 25th century gender is ignored in favour of they, and then assigning his or her based not on genitalia, but on the role and personality of the person. This would be great, except she is at great pains to explicitly tell the reader whenever she deliberately miss-assigns gender, even in situations where it is obvious. Contrast this with Ancillary Justice, where the constant confusion of gender is used seamlessly and subtly anchors the book.

Worse, about two thirds of the way through the book there is a turn. While it is not out of character with the rest of the story, it introduces a lurid element and highlights the underlying cynicism of Too Like the Lightning. While it is difficult to assess the morality of what is explicitly the first half of a duology, and it possible that dominos are being set up to be knocked down, I strongly disliked the direction it was taking, and the implications it was making: an emphasis on great people, a look at the incestuousness of power, and the casual embrace of violence for the greater good. I want to know what happens in the end, but I won’t read the sequel.

A technical tour de force of future science fiction crossed with theology written as an 18th century narrative, that I found hollow and callous.

Laurie Penny

Everything Belongs to the Future [Short work]

Social activists oppose a social order where the rich and famous will live for ever, and no body else will.

Future’s where the rich and powerful hoard anti-agapic drugs are pretty common. What makes this one stand out it how well it captures the perspectives of those fighting the social order – not heroes or terrorists, but garden variety social activists. It does this while providing trenchant criticism of a wide variety of social issues without ever feeling preachy, and hits all it’s targets in a very svelte page count.

Science Fiction as social criticism with teeth that finds a perfect length.

The Killing Jar and Blue Monday [Short works]

Two stories of soft dystopia’s, that is ones that are terrifyingly close to the real world.

Both of these stories cover similar ground – worlds where entertaining the populous has pushed to government to make small, but terrible changes to the world. Obviously there is an element of satire here, attacking social trends through absurdity, but they are set apart by the relatable nature of their protagonists: initially normal seeming people who do terrible things for a living.

Two neat little stories of normal people with terrible jobs.

Your Orisons May Be Recorded [Short work]

An angel at the end of your prayers gets run down by the world.

Manning a help line would suck, manning it for all eternity without actually being able to help would be, well hell. A character study of an angel, trapped in cubicle hell, whose only friend is a chilled out demon.

Enjoyable tale of an Angel being ground down by the grind of office culture.

Kelly Robson

Waters of Versais [Short work]

An ambitious courtier runs the plumbing of Versais with the help of a water spirit.

A novel story with a strong sense of time and place (18th Century Versailles) , that is ultimately a character study about a man who thinks he craves success and power, but needs something else.

A great little read.

Two-Year Man [Short work]

A janitor takes a baby home from the waste at his lab.

Painfully sad sf story.

The Three Resurrections of Jessica Churchill [Short work]

A strange force brings a girl back to life, again and again.

Brutal short about murder and sacrifice.

Malka Older

The Black Box [Short work]

The life of a woman with a built in black box.

This is not a new premise, but it’s well executed, and the ending is very good.

The Rupture [Short work]

A student decides to come to a dying earth for uni.

This is a strange little story – the world is dying, but people choose to stay, and with the end some way off, some people choose to visit.

Ultimately, it’s the tried and tested “what it means to be human”, but spun into a going to college narrative.

Tear Tracks [Short work]

First contact goes well, but provides a painful reminder of the past for one of the human delegates.

This reminded me of a much better, much more empathetic version of “On the Uses of Torture” by Piers Anthony. A couple of astronauts on a first contact mission find an alien society that is very similar, to ours, but differs in how it appoints people to positions of power, which in turn causes one of the Astronaut’s to re-examine their past. It’s not subtle, but it is very well drawn and never feels didactic.

A well drawn tale of empathy for those hurt by life.

Infomocracy [Novel]

A look at a world of micro-democracy: divided into electorates of 100,000 people governed by whoever wins the electorate.

Infomocracy is a book examining an idea – radical micro-democracy. In SF, these sorts of stories are often best at shorter length, as an idea is not enough to sustain a novel on it’s own. Fortunately, Older avoids this trap by writing a solid thriller of electoral shenanigans centered on a handful of well-drawn characters, that would be entertaining for anyone not interested in speculative election systems.

For those of us who are interested in such things, Infomocracy is fascinating. Every part of micro-democracy is explored, from the sorts of parties that would form to how cities would function. More importantly, we get to see the warts of such a system, from corporations levering wealth to gain power, to parties making conflicting promises in different territories to win more seats. Older even takes the time to deal with some of the issues of how to get from here to there, disposing of guns in the fiction and alluding to nukes and security.

A really good thriller that also provides a detailed examination of an interesting idea.

Sarah Gailey

Haunted [Short work]

A short story about a house who is haunted.

This is better than any of the hugo short story nominees. It tells a melancholic tale about the aftermath of domestic violence from a unique perspective, and it does it in a ridiculously short length.

Great.

Stars [Short work]

An injured woman dreams about a lake of stars.

Simple tale about passing over with a strong ending.

Hugo Ballot

1. Laurie Penny

2. Malka Older

3. Sarah Gailey

4. Kelly Robson

5. Ada Palmer

6. No award

7. J. Mulrooney

This was a tough category to rank: I could have ranked the first three in any order and still not been happy. “Haunted” is the best short story I read for the Hugos, “Infomocracy” and “Tear Tracks” demonstrated huge versatility for a new writer, but the four stories from Penny were the best overall. I also really liked the “Waters of Versailles”, but Robson didn’t quite hang with the other three.

I am however, almost certain that “Too Like the Lightning” will win this category, and I can’t say it won’t be deserved, just that I really didn’t like it. As for Mulrooney, the book is terrible, and I would be depressed by a win, but the problem with parody is a near miss is possibly worse than an out and out failure – I can imagine a future where someone recommends a future book and I enjoy it.

2 thoughts to “Hugo Awards Extravaganza 2017 – John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer”