- Rivers of London

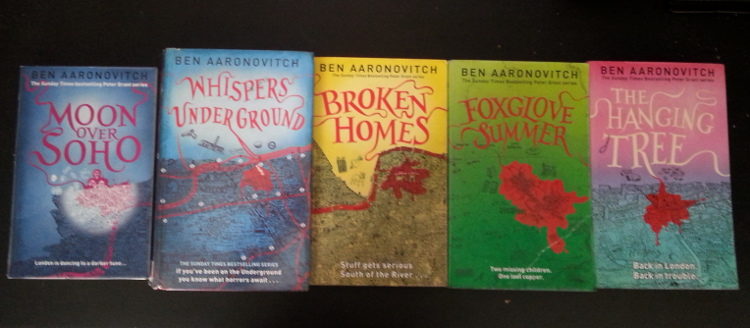

- Moon over Soho

- Whispers Under Ground

- Broken Homes

- Foxglove Summer

- The Hanging Tree

A member of the filth finds his calling as the police’s newest, and nearly only, wizard.

Peter Grant is not your typical urban fantasy protagonist. For starters he’s a cop, and an extremely junior one at that. More importantly, at the beginning of the series, not a very good cop: better than a hanger,1 but lacking in the instincts and discipline that would make him stand out. He’s also black, which matter less then it might have in the past, but certainly carries varying degrees of baggage in the Police, London, and England respectively.

However, where Peter Grant excels as a character is in his perspective. In Rivers of London, the first thing that hits you is the depth of knowledge of London’s urban planning and architecture, and inseparable from that in a city as important as London, it’s history. As the books go on, the same level of attention is lavished on police work; not just the flashy stuff, but the nuts and bolts organisation and administration of a cop shop as big as the Met. Whether discussing architecture or policing however Peter’s tone is never didactic, instead the former is always delivered with enthusiasm, and the later with cynical resignation.

This ties in with the big picture of his character – he always disparagingly claims that he would have been an architect if he could draw or a scientist if he was better at math, but he chose to be a cop to help people. Throw in realistic relationships with his partner, mentor, parents (and since his mother is from Sierra Leone, his greatly extended ‘family’), and the various rivers of southern England, and you have one of the most human characters to appear as the protagonist of an urban fantasy novel. He’s the right person in the right place, rather than a destined hero. This in turn defines the tone of the books: even when dealing with death and destruction, there is a light touch and a sense of fun to the stories.

Beyond Peter Grant, the series benefits from a wide degree of variation between the books. Each book in the series addresses different crimes (though to be fair, usually some form of murder), in different parts of London, and even though there are overarching plot elements and strong character development, they don’t blur together. Key to this is the obsessive knowledge conveyed on the topic at hand: be it the history of Jazz in London, the underground, or London’s estates. 2 This is best illustrated by Foxglove Summer, where Peter Grant leaves the city to check out a missing person’s case in the country, providing both him, and the reader, with a break from the grand plot, while getting into the details of how the English handle such a case.

Also important is the judicious pace in world building. Peter is the first wizard’s apprentice in a long time, because there was an assumption that magic was fading away. The elements of the hidden world; rivers, fey, and wizards, all feel like they could hide under the surface of London, and often only reveal themselves after they’ve been poked, allowing for a gradual introduction. Peters very presence changes the game, from the small, a young girl who hears what he does from his Mum (witch catcher) and decides she want to become one, to the large, unearthing London’s hidden magical underworld. As for the magic itself, it has been systematised by the wizards, but not understood, giving the author great latitude to doll out how it works as Peter figures it out by applying the scientific method.

The final element that is key to the series success is it’s supporting cast: Lesley, Dr Walid, DS Stephanopoulos, Tyburn, Abigail, and others are all great characters with distinctive personalities and understandable motivations. However the Nightingale, Peter’s master, would be a standout character in any novel. Here the careful pacing of the books bears wonders, and we build up a picture of a gentleman wizard, tempered by the horror of world war 2, who has survived and prospered by being willing to adopt anything that he percieves as useful, and ignoring the rest. Underlying all this is a deep well of compassion: a character who has seen the worst of humanity and decided he could make the world better by helping people.

Less important, but still worth noting – the UK cover art for the series is phenomenal: stylised and anotated maps of the relevant areas.

If I were to make a couple of minor complaints about the series, they would go to the structure and plots of the books. You can tell Aaronovich comes from TV writing, as each book has an A and B story, which sometimes intersect, and sometimes act in apposition on the characters. Unfortunately one plot often feels weaker than the other, and the structure itself is repetitive. The other is that the escalation of events, particularly the endings of Broken Homes and The Hanging Tree, seem like they should be drawing more attention, if not from the media, then at least from within the government bureaucracy.

Still, on the whole, the Rivers of London series is excellent, and I look forward to next volume, where I hope to see what a stakeholders meeting for the Mets wizarding department looks like.

Superior urban fantasy with a strong sense of place, excellent characters, careful world building, wizards, and coppers.